What Is Large Cell Lung Cancer?

Large cell lung cancer is a less common type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It can also be more aggressive than some other subtypes.

Jump to:

- Understanding Large Cell Lung Cancer

- How common is it?

- Where does it occur, and why do people call it “aggressive”?

- Symptoms and early warning signs

- Causes and risk factors

- How is large cell lung cancer diagnosed?

- Imaging

- Getting tissue

- Pathology and additional testing

- Staging

- Treatment options

- Surgery (for suitable early-stage disease)

- Radiotherapy, including SABR

- Systemic treatment

- Prognosis and why subtype matters, but not as much as you think

- When to seek medical advice

The name is not very glamorous. It basically comes from what the cells look like under a microscope. They look large, abnormal, and not very “neat” in the way some other lung cancer cells can be.

The useful bit will help you understand what it means in practice, what usually happens next, and what your options tend to look like.

Understanding Large Cell Lung Cancer

Large cell lung cancer sits under the umbrella of NSCLC, alongside adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

What makes it different is this.

Pathologists often use the term when the cancer does not have the clear features that would label it as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell cancer. In other words, it is sometimes defined by what it is not, rather than a classic pattern it is.

That can sound vague. To be honest, it sometimes is. Diagnosing subtypes can be surprisingly nuanced, and it depends on the quality of the sample, the stains used, and the specific appearance of the cells.

One important exception is large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is usually treated more like a neuroendocrine cancer and can behave more aggressively. If that wording appears in a report, it is worth asking the team to explain what it means for treatment planning.

How common is it?

Large cell lung cancer is less common than adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. You will often see figures quoted around 10 to 15 percent of NSCLC, although the exact number varies between studies and has shifted over time as pathology testing has improved.

The main point is not the percentage. The main point is that it is recognised, it is treatable, and we plan treatment based on the full picture, not just the label.

Where does it occur, and why do people call it “aggressive”?

Large cell cancers can arise in different parts of the lung. They are often described as being more likely to occur towards the outer parts of the lung, although that is not a rule.

They can be labelled “aggressive” because they may grow and spread faster than some other NSCLC tumours. That is one reason they are sometimes diagnosed at a later stage.

That said, stage still matters more than subtype. Every time. A small cancer found early is a very different situation from a cancer found after it has spread, whatever the histology says.

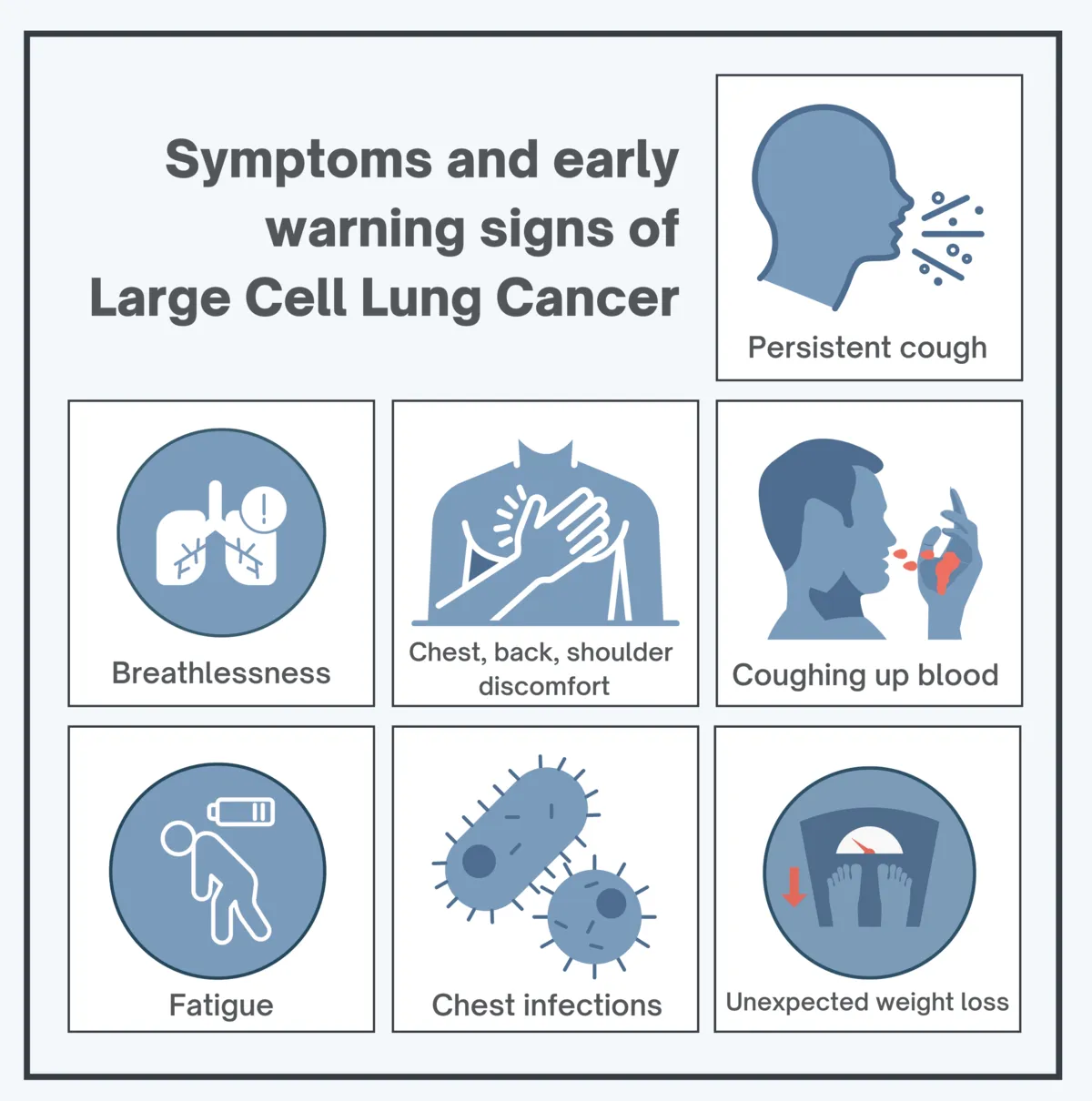

Symptoms and early warning signs

Symptoms overlap heavily with other lung cancers and, frankly, with lots of everyday conditions.

That is what makes this hard.

Common symptoms include:

-

A persistent cough, or a cough that changes in character over a few weeks

-

Breathlessness that is new, or clearly getting worse

-

Chest, back, or shoulder discomfort that does not settle

-

Coughing up blood, even small streaks

-

Fatigue that feels out of proportion

-

Unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite

-

Repeated chest infections, especially if they keep coming back

None of these is specific to cancer. I mean, if they were, the job would be much easier.

What matters is persistence and change from your usual baseline. If something is lingering for weeks, worsening, or stacking up with other symptoms, it deserves to be evaluated by a lung oncologist.

Causes and risk factors

Smoking is the biggest risk factor for lung cancer overall, including large cell cancer. The longer and heavier the exposure, the higher the risk.

But it is not the only factor, and it is not a morality tale.

Other things we take seriously include:

-

Second-hand smoke exposure over the years

-

Occupational exposures, including asbestos and certain industrial dusts or fumes

-

Radon exposure, depending on where you live and work

-

Air pollution, particularly long-term exposure

-

Age, with most diagnoses later in life

-

Family history, which can slightly increase risk in some cases

And yes, lung cancer can occur in people who have never smoked. It is less common, but it happens. Symptoms still count.

How is large cell lung cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis usually starts in one of two ways. Symptoms that do not settle, or something picked up on imaging for another reason.

From there, the process is typically step-by-step.

Imaging

A chest X-ray is often the first test in primary care. If there is ongoing concern, a CT scan is usually the next key step because it gives a much clearer view.

A PET-CT is sometimes used to assess metabolic activity and look for disease elsewhere. It can be very helpful. It is not magic. Inflammation and infection can also light up.

Getting tissue

To confirm large cell lung cancer, we usually need a biopsy, meaning a sample of tissue looked at under a microscope.

How the sample is taken depends on where the lesion sits and what is safest:

-

Bronchoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) for samples via the airways

-

CT-guided needle biopsy for some peripheral lung lesions

-

Less commonly, a surgical biopsy is performed if other routes are not suitable

Pathology and additional testing

Once a diagnosis is made, modern practice often includes immunohistochemistry and sometimes molecular testing to look for markers or genetic changes that may influence treatment.

This is particularly important because treatment is not just “chemo or not chemo” anymore. In the right situation, targeted therapies or immunotherapy can make a real difference.

Staging

Staging is about understanding where the cancer is and whether it has spread. It usually involves imaging, sometimes sampling lymph nodes, and occasionally further scans, depending on the case.

It sounds like box-ticking. It is not. Staging is what allows us to recommend the right treatment with a straight face.

Treatment options

Treatment is personalised. It depends on stage, overall health, lung function, and the tumour’s biology.

Most decisions are made through a multidisciplinary team. That is as it should be. Lung cancer care is not a one-person sport.

Common options include:

Surgery (for suitable early-stage disease)

If the cancer is localised and a person is fit for surgery, an operation can remove it with curative intent. The exact type of surgery depends on location and lung function.

Radiotherapy, including SABR

Radiotherapy can be used in different ways:

-

SABR for some small, localised tumours, often when surgery is not ideal

-

Conventional radiotherapy in other settings, sometimes combined with chemotherapy

Systemic treatment

This includes:

-

Chemotherapy, in early-stage settings (before or after local treatment) or for more advanced disease

-

Immunotherapy is now part of standard care for many patients, depending on stage and tumour markers

-

Targeted therapies, when specific actionable mutations are present

If you are reading this and thinking “that sounds like a lot”, you are not wrong. The upside is that we have more tools than we used to. The other truth is that choosing the right sequence can be bloody hard. That is why good staging and good pathology matter so much.

Prognosis and why subtype matters, but not as much as you think

People naturally want a number. A percentage. A neat prediction.

In reality, outcome is driven far more by stage at diagnosis than by whether the report says large cell, adenocarcinoma, or squamous.

Large cell histology can be associated with faster growth. That is relevant. But it does not override the basics.

Early-stage disease can often be treated with curative intent. Later-stage disease is still treatable, and outcomes continue to improve with modern radiotherapy and systemic treatments, but it is usually a longer road.

When to seek medical advice

Please speak to your GP or treating team if you have:

-

A cough or breathlessness persisting beyond a few weeks

-

Chest discomfort that is ongoing or worsening

-

Any coughing up blood

-

Unexplained weight loss, persistent fatigue, or recurrent infections

Most people who get checked will not be diagnosed with lung cancer. That reassurance is valuable too.

And if it is lung cancer, getting clarity sooner usually means more options and a more controlled plan.