How Successful is Stereotactic Radiotherapy?

Stereotactic radiotherapy (SABR or SBRT) is one of those treatments that sounds futuristic, but is actually now routine in many UK centres.

Jump to:

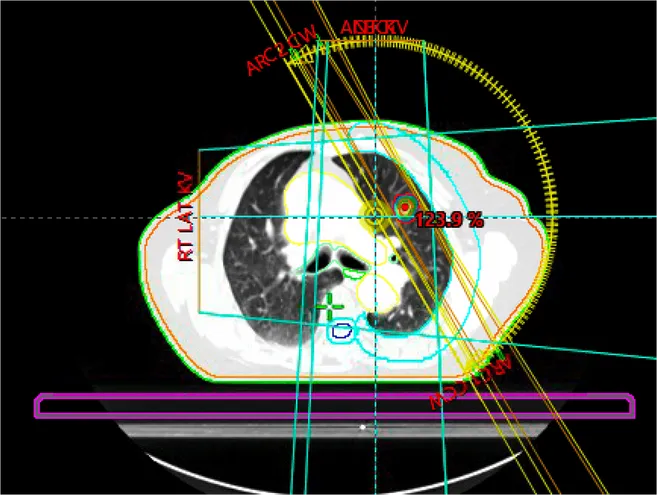

It’s a way of giving radiotherapy to a tumour from lots of different angles so the beams meet at the tumour. The point is simple. High dose to the cancer, much lower dose to the surrounding normal tissue. That usually means better tumour control with fewer side effects than “older style” radiotherapy.

So, how successful is it?

To be honest, the answer is that it is often very successful in the right scenario. But “success” means different things depending on why we’re using it.

What do we mean by “successful”?

When doctors talk about success with stereotactic radiotherapy, we usually mean one (or more) of these:

-

Local control: has the treated tumour stayed controlled in that exact spot?

-

Symptom control: has it reduced pain, breathlessness, cough, bleeding, or pressure symptoms?

-

Survival: has it helped people live longer (this is much harder to prove, and depends on the cancer type and stage

-

Quality of life: Is the benefit worth the disruption and the side effects?

Most of the strongest data for stereotactic radiotherapy is around local control, and it’s genuinely impressive when it’s used in the right setting with careful planning and follow-up, which is exactly what we focus on with stereotactic radiotherapy.

It’s also worth being clear about intent. When stereotactic radiotherapy is used to treat a primary tumour (rather than a metastasis), it is often delivered as a curative treatment, aiming to eradicate that tumour in that location.

Success in early-stage lung cancer

In early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stereotactic radiotherapy is widely used, especially when surgery isn’t possible or isn’t a good idea.

A large multicentre study of medically inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with SBRT reported 5-year outcomes of 9.6% for local recurrence and 9.8% for regional recurrence. Distant metastasis occurred in up to about 15% of patients. Overall survival was around 70% in that study, although survival varies widely depending on age, other illnesses, and overall health.

That local recurrence figure is the key one. It suggests that in many patients, the tumour stays controlled in the treated area long term. Survival data can be hard to interpret with SABR. Often people who have SABR rather than surgery have other serious health problems that can shorten their survival even if they are cancer-free.

Now, just to keep us grounded. Overall survival in lung cancer is influenced by lots of things beyond the tumour we treat (other lung diseases, smoking-related heart disease, future new lung cancers, spread elsewhere).

So local control is often the cleanest measure of “how well did the treatment do its job”, and it’s also why getting the right lung cancer diagnosis (including accurate staging and a clear plan) matters so much before deciding which treatment is best.

Success in oligometastatic cancer

This is the other big growth area.

If someone has cancer that has spread, but only to a limited number of sites, we sometimes use SABR to ablate (destroy) those spots. The question is whether that helps people live longer, not just control a scan.

A randomised phase II study with long-term follow-up showed a 5-year overall survival of 42.3% with SABR, compared with 17.7% with standard treatment. Median overall survival was 50 months with SABR versus 28 months without. Treatment-related toxicity was higher with SABR, with grade 2 or above adverse events reported in 29% of patients compared with 9% without SABR. A small number of treatment-related deaths were also reported in the SABR arm, with 3 deaths (4.5%).

That’s a big deal. It doesn’t mean SABR is right for everyone with stage 4 cancer. But it does show that, in carefully selected patients, treating a few metastatic sites aggressively can double the chance of somebody with Stage 4 cancer being alive in 5 years’ time.

In practice, this works well when the decision sits inside a personalised treatment plan for metastatic disease, one that weighs up where the cancer is, how fast it’s behaving, what systemic treatments are available, and what we’re trying to achieve overall.

What affects the success rate?

This is where things get a bit more “real life”.

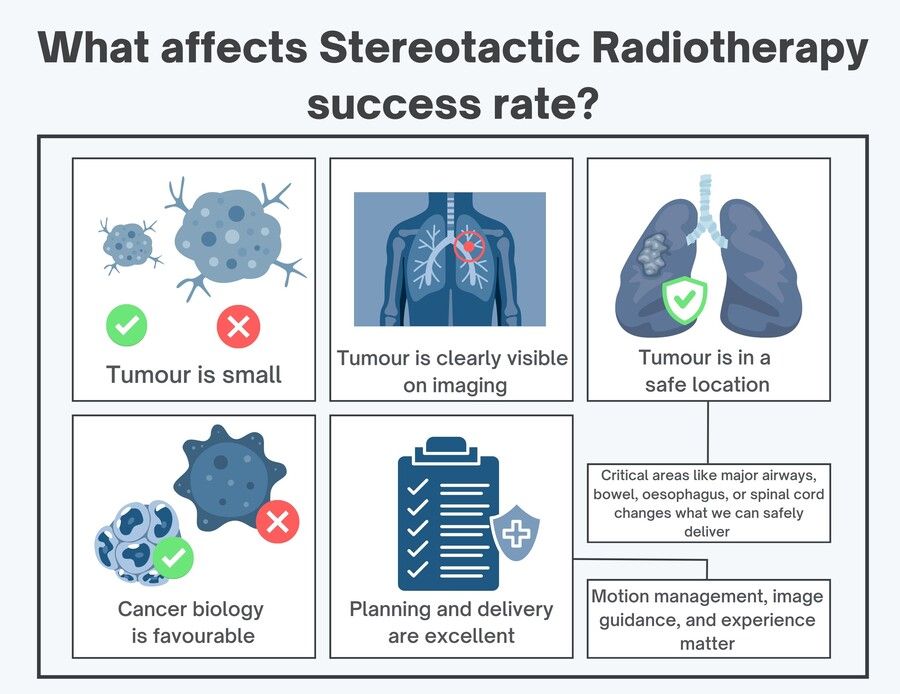

Stereotactic radiotherapy tends to work best when:

-

The tumour is small (success drops as lesions get larger)

-

The tumour is clearly visible on imaging (so we can target it properly)

-

It’s in a safe location (close to major airways, bowel, oesophagus, or spinal cord changes what we can safely deliver)

-

The cancer biology is favourable (some cancers behave more aggressively than others)

-

The planning and delivery are excellent (motion management, image guidance, and experience matter)

In other words, it’s not just “a machine”. It’s the whole system around it.

What about side effects?

One of the main advantages of stereotactic radiotherapy is that it’s highly precise, so we can deliver an effective dose to the tumour while limiting radiation to nearby healthy tissues.

Side effects depend largely on where the tumour is, how close it is to sensitive structures, and how much surrounding normal tissue has to be included for safety.

Lung lesions near the chest wall can sometimes lead to chest wall soreness, nerve irritation, or (more rarely) a rib fracture.

Tumours close to central structures (such as major airways, the oesophagus, or large blood vessels) may carry different risks, which is why we sometimes adjust the dose or spread treatment over more sessions.

The key point is this: good stereotactic treatment isn’t just about the machine, it’s about careful planning, daily accuracy checks, and a clear, individualised explanation of the realistic benefits and downsides for your specific situation.

When should you ask about SABR/SBRT?

It’s worth asking if you (or someone you’re caring for) has:

-

Early-stage lung cancer and surgery are not straightforward

-

A small number of metastases (oligometastatic disease)

-

Cancer that is mostly controlled but growing in one or two spots (oligoprogression)

-

A need for a highly targeted approach because nearby organs make standard radiotherapy difficult

If you’re being told “it’s palliative only”, that may still be correct. But it’s also the moment to ask: is there a role for stereotactic treatment anywhere in this plan?

The bottom line

Stereotactic radiotherapy is “successful” because it does what radiotherapy has always wanted to do: treat the cancer hard, and leave everything else alone as much as possible.

But it’s not a magic wand. The best outcomes come from good patient selection, careful planning, and treating the right target for the right reason.