Does lung cancer cause pain, and where might you feel it?

People often ask whether lung cancer causes pain, and if it does, where you would actually feel it.

Jump to:

- Understanding lung cancer pain

- Common places you might feel pain

- Chest

- Shoulder and arm

- Back

- Bones (ribs, spine, hips)

- Head or neck (less common)

- What influences whether someone gets pain?

- When should pain make you think about lung cancer?

- How do we relieve lung cancer pain?

- Prevention and early detection

- What happens next?

- Start with the basics

- Check for red flags

- Decide how urgently to act

- Be ready for the key questions

- Ask for a clear plan

- Do the sensible, supportive things while you wait

- About Dr James Wilson

The honest answer is that it can, but many people do not get pain early on. When pain does happen, it is usually because the cancer is irritating the lining of the lung, involving the chest wall, pressing on nerves, or spreading to somewhere like the bone.

In this guide, I’ll talk you through the common patterns I’ve seen, what else can look and feel similar, and what we can do next to get you checked and more comfortable.

Understanding lung cancer pain

Pain from lung cancer is usually caused by one of a few things:

-

Pressure or invasion: A tumour can press on, or grow into, nearby structures in the chest.

-

Irritation of the pleura (the lining around the lung): This can cause a sharper pain that is worse when you breathe in, cough, or move.

-

Inflammation: Cancer can trigger local inflammation that makes tissues sore and sensitive.

-

Spread (metastasis): Particularly to the bone, which can be very painful.

People describe it in different ways. Some get a dull ache. Some get a sharp, catching pain. Some notice it only when they take a deep breath, laugh, or climb stairs.

One important point to remember: Small-cell lung cancer tends to grow and spread faster, and symptoms can appear sooner. Non-small cell lung cancer is more common and often progresses more slowly, which is one reason it can be quiet and non-eventful early on.

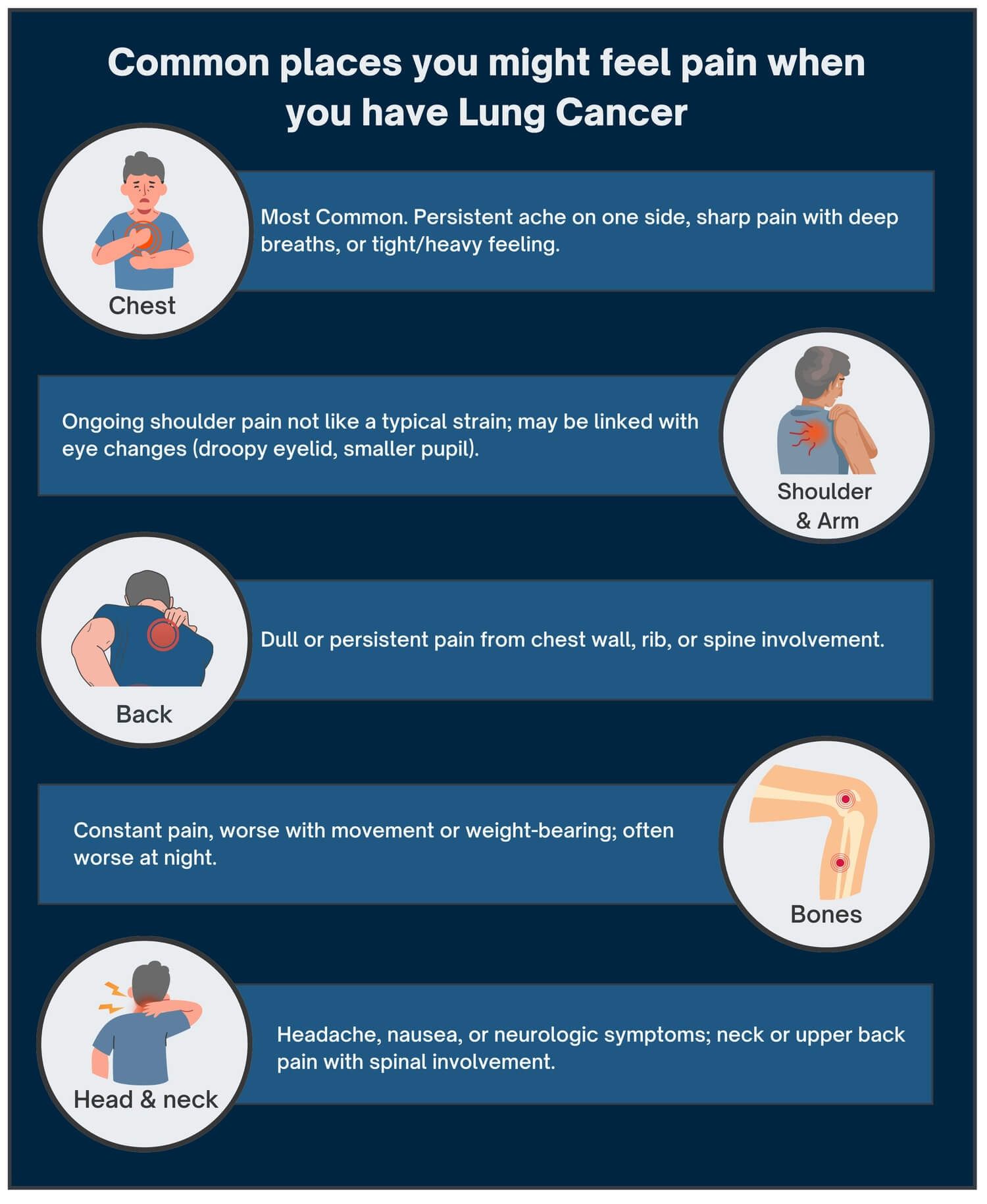

Common places you might feel pain

Chest

This is the most common site.

It may feel like a persistent ache on one side, a sharper pain that worsens with a deep breath (often called pleuritic pain), or a general sense of tightness or heaviness. Tumours close to the outer edge of the lung are more likely to irritate the pleura or chest wall. More central tumours can cause discomfort by irritating the larger airways.

Shoulder and arm

Some tumours at the very top of the lung (called Pancoast tumours) can irritate nerves that run into the shoulder and arm. This can feel like shoulder pain that does not behave like a normal strain. Occasionally, it comes with other signs, such as a droopy eyelid or a smaller pupil on one side.

Back

Pain can be felt in the back if the chest wall is involved, or if it directly invades or spreads to the ribs or spine.

Bones (ribs, spine, hips)

If lung cancer spreads to the bone, the pain often becomes more constant, tends to worsen with movement or weight-bearing, and can sometimes be worse at night.

Head or neck (less common)

Headache, nausea, or neurological symptoms can happen if it spreads to the brain. Neck or upper back symptoms can occur with spinal involvement.

What influences whether someone gets pain?

A few things tend to make pain more likely.

Stage matters. Early cancers in the middle of the lung often cause no pain at all. More advanced disease is more likely to occur, simply because there is a greater chance of something being irritated or compressed.

Location matters too. Pain is most often triggered when the pleura, the chest wall, or nearby nerves are involved.

Other lung problems can muddy the waters. If someone already has COPD or a chronic cough, there can be background chest wall discomfort anyway, which makes it harder to tell what is new.

And then there is individual variation. People describe pain very differently, and thresholds vary. So we try not to get hung up on one word like “ache”. We look at the overall pattern.

When should pain make you think about lung cancer?

Most chest pain is not lung cancer. Muscular strain, reflux, infections, and anxiety can all cause very convincing symptoms.

That said, I would take it seriously and advise you to speak to your GP if pain is persistent and progressive (more than 2 to 3 weeks), especially if it occurs alongside any of the following:

-

coughing up blood

-

unexplained weight loss

-

worsening breathlessness

-

a new, persistent cough

-

hoarseness

-

recurrent chest infections

If you have a significant smoking history, it is worth having a lower threshold for getting checked. Not because it is definitely cancer, but because it is sensible.

How do we relieve lung cancer pain?

If pain is caused by cancer, we can almost always improve it. Often significantly.

Options might include:

-

Simple painkillers (paracetamol, anti-inflammatories if safe for you)

-

Stronger pain relief, including opioids when needed, titrated carefully

-

Radiotherapy, which can be very effective for painful bone deposits or chest wall involvement

-

Nerve pain treatments (for example, medications used for neuropathic pain)

-

Specialist pain procedures (nerve blocks) in selected cases

-

Supportive input from palliative care, which is about comfort and function, not “giving up”

The best approach is usually a combination, reviewed regularly.

Pain can have a tremendous impact on your well-being. Getting on top of pain, and improving your quality of life - including how much you can do each day - is often the first step to treatment in lung cancer.

Prevention and early detection

The biggest risk reduction is still not smoking, or stopping if you do. I know that can sound a bit repetitive, but it is repetitive because it is true. The benefit starts quickly, and it keeps building over time. If you have tried before and it has not stuck, that does not mean it is hopeless. It usually just means you have not had the right support yet.

In the UK, we also have targeted lung health checks for people at higher risk. These programmes are designed to pick up early changes, often before symptoms like pain, breathlessness, or weight loss show up. They typically use a risk questionnaire and, for those who meet criteria, a low-dose CT scan.

If you think you might qualify, it is worth asking your GP, or you might prefer to consult with an oncologist. As a rough guide, checks are often aimed at people in their mid-50s to mid-70s who smoke now or used to, particularly if they smoked for many years. Even if you do not meet the criteria, it is still worth discussing any persistent chest symptoms early. The aim is not to frighten people into scans. It is to catch problems while they are still small and more treatable.

A few other practical steps help too: keep on top of vaccinations if you are prone to chest infections, don’t ignore a cough that changes and does not settle, and mention any relevant exposures (like asbestos or heavy dust exposure) when you see your GP. Small details can make a big difference to how quickly we join the dots.

What happens next?

Lung cancer can cause pain, but pain is not always an early sign, and it is not specific to cancer either. What matters is the pattern, how long it has been going on, and whether there are other red flags alongside it.

Here’s a quick, practical plan:

Start with the basics

-

Note where the pain is (chest, shoulder, back, ribs, arm).

-

Track how long it has been going on and whether it is getting worse.

-

Write down what it feels like (dull, sharp, burning, “catching” on a deep breath).

-

Notice triggers: worse with breathing in, coughing, movement, lying flat, or after exercise.

Check for red flags

-

Coughing up blood (even a small amount).

-

A new cough that is not settling, or a clear change in a long-standing cough.

-

Breathlessness that is new or worsening.

-

Unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, or persistent fatigue.

-

Hoarseness that lasts more than a couple of weeks.

-

Chest infections that keep coming back or that are slow to clear.

-

New shoulder and arm pain with tingling, weakness, or a droopy eyelid on one side.

-

Persistent bone pain, especially in the ribs or spine, worsening at night.

Decide how urgently to act

If you have severe chest pain with breathlessness, you feel faint, or you are coughing up a lot of blood, call 999 or go to A&E. If you have any of the red flags we have mentioned, or pain that is persistent and unexplained, speak to your GP urgently, ideally on the same day. If the pain is mild, clearly muscular, and improving, it is reasonable to book a routine GP appointment, but still bring it up if it keeps returning.

Be ready for the key questions

Before your appointment, it helps to be ready for a few key questions. Your clinician will usually ask about your age and your smoking history, including roughly how many years and how much. They will also want to know about any past lung problems, such as COPD, asthma, TB, or pneumonia, plus your work and exposure history, including asbestos, dusts, or fumes. Do mention any personal history of cancer and any relevant family history. Finally, let them know whether you have had any recent imaging already, such as a chest X-ray or CT scan, and what you were told about the results.

Ask for a clear plan

If symptoms persist or your risk is higher, ask whether further investigation is needed. This may include a chest X-ray as a first step, and whether it should be arranged urgently. If the X-ray is abnormal, or if your symptoms and risk factors justify it, a CT scan may be appropriate.

You should also ask whether you meet the criteria for referral through the urgent suspected cancer pathway. If tests come back normal but symptoms continue, clarify what the next step will be and the timeframe for review, rather than accepting a vague “wait and see” approach.

Do the sensible, supportive things while you wait

While you’re waiting, it’s worth doing the sensible, supportive things. Use simple pain relief if it‘s safe for you, and your pharmacist or GP can advise on what is appropriate. If you smoke, stopping now genuinely helps, even if it is only in the short term. And if anxiety is ramping up, say so. Waiting is often the hardest part, and it’s something we can support you with.

About Dr James Wilson

Dr James Wilson is a consultant oncologist specialising in lung cancer and advanced radiotherapy. Based in Central London, he works full-time in private practice, aiming to provide rapid diagnosis, clear plans, and calm, practical guidance when time matters.