Coughing up white phlegm with lung cancer: What it can mean

Coughing up white phlegm can be unsettling, especially if lung cancer is already part of the picture. People often assume phlegm means infection. Sometimes it does. Sometimes it is simply irritation. And in the context of lung cancer, it can also be a clue that something is affecting the airways and how mucus clears.

Jump to:

- What does white phlegm actually mean?

- How lung cancer can lead to white phlegm

- Partial blockage of an airway

- Irritation and inflammation in the airways

- Predisposition and Treatment

- Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (IMA)

- Other common causes that still matter, even when cancer is present

- When should white phlegm worry you?

- How we assess it (The UK approach)

- What helps (Symptom control and treatment)

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Can white phlegm mean my lung cancer is getting worse?

- What if the phlegm turns yellow or green?

- What if there is blood in the phlegm?

- Why is it worse at night or in the morning?

- When should I contact my cancer team rather than my GP?

- Next steps

- About Dr. James Wilson

In this article, we take a look at what white phlegm usually represents, how lung cancer can contribute to it, what else can cause it, and what we typically do about it in the UK.

What does white phlegm actually mean?

Phlegm (sputum) is mucus produced by the lining of the airways. A small amount is normal. It is part of how the lungs trap dust, particles, and microbes and move them back out again.

White phlegm is usually:

-

Clear to cloudy white

-

Sometimes frothy

-

Usually not foul-smelling

-

Not obviously infected-looking (Which is more often yellow or green)

When it becomes persistent, thicker, or more frequent, it usually points to ongoing airway irritation or poor clearance, rather than one specific diagnosis. The pattern matters more than the colour alone.

A few practical details we always ask about include how much there is, how thick it is, whether it is worse in the morning, and whether you can clear it or feel as if it is “stuck”. Perhaps the important question we ask is, “Do you feel unwell?”

If something has clearly changed and you are not getting a straight answer, it is worth getting it properly checked by a lung cancer specialist. We can review your symptoms, look at any recent imaging, and set out a clear plan for what happens next.

How lung cancer can lead to white phlegm

In people with lung cancer, white phlegm most often happens for fairly straightforward reasons.

Partial blockage of an airway

A tumour can narrow a bronchus, any of the major air passages of the lungs that diverge from the windpipe, which means mucus does not drain and clear as efficiently. It pools behind the narrowing and then gets coughed up. Early on, that sputum is often white. If infection develops behind the blockage, the sputum may change to yellow or green.

Irritation and inflammation in the airways

Cancer and the local inflammation around it can make the airway lining more irritable. That irritation can increase mucus production and trigger coughing. You can end up coughing more mucus even without a true infection.

The tumour itself can also leak fluid, which can be coughed up like phlegm.

Predisposition and Treatment

Some people with lung cancer may also have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic bronchitis, particularly if they have a history of smoking. Those conditions already predispose one to daily sputum, and the cancer can tip things into a more noticeable change.

Radiotherapy and some systemic treatments can irritate airways in the short term. That does not mean the treatment is “not working”. It just means we sometimes need to manage symptoms alongside it.

Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (IMA)

The lung cancer that produces the most phlegm, often resulting in a rare, debilitating condition called bronchorrhea (defined as the production of more than 100 mL a day of watery sputum), is Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (IMA), a type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Historically, this was known as bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, though this term is rarely used now. These days, we tend to describe the subtype more precisely, and IMA is the term you are more likely to hear. It arises from terminal bronchiolar or acinar cells, growing along alveolar structures without vascular/pleural invasion.

When it happens, it can be genuinely exhausting, not just because it is unpleasant, but because it can disrupt sleep, trigger persistent coughing, worsen breathlessness, and make hydration and nutrition harder to maintain.

If someone is producing a lot of watery sputum, the key is not to self-diagnose from that fact alone, but to flag it early and seek a consultation, so we can assess what is driving it and treat the symptom properly.

In practice, we would also be thinking about other causes of excess sputum and breathlessness, including infection and fluid overload, and we would want the right imaging and respiratory assessment alongside the cancer work-up.

Other common causes that still matter, even when cancer is present

Even if someone has lung cancer, white phlegm is often due to something else happening at the same time. It can be caused by a viral respiratory infection, which often starts with clear or white sputum.

COPD flare-ups and chronic bronchitis can do the same, and asthma can produce thick, sticky white mucus that is hard to shift. Post-nasal drip from sinus problems or allergies is another common reason. Reflux, also called gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or GORD, can irritate the throat and airways, particularly overnight. Dehydration can make mucus thicker and more difficult to clear. Less commonly, fluid overload or heart failure can cause frothy sputum, sometimes with a pink tinge.

So, yes, white phlegm can appear with lung cancer. But it is not a lung cancer-only symptom. We still have to think clinically and not jump to conclusions.

When should white phlegm worry you?

White phlegm on its own is rarely an emergency. In the context of lung cancer, the main concern is what comes with it, and whether it represents a complication like infection or airway obstruction.

Speak to your cancer team or GP promptly if you notice any of the following:

-

A clear change in your usual cough or sputum pattern lasting more than 2 to 3 weeks

-

Breathlessness that is new or worsening

-

Chest pain, particularly if it is new, persistent, or pleuritic (Worse on breathing in)

-

Fever, sweats, or feeling systemically unwell (Possible infection)

-

Coughing up blood, even small amounts

-

Unexplained weight loss or significant fatigue beyond what is expected

-

A new hoarse voice that does not settle

If you are already under an oncology or respiratory team, you do not need to wait and see how bad it gets. Tell us. This is exactly the sort of thing we want to hear about early.

How we assess it (The UK approach)

What we do depends a bit on where you are in your lung cancer pathway and what else is going on at the time.

We usually start with a careful symptom history and an examination, including your oxygen levels. If there are any signs that infection or inflammation might be part of the picture, we may add blood tests. A chest X-ray can sometimes be useful too, although it depends on what your baseline imaging already shows.

If we need a clearer view, we will usually move to a CT scan. That helps us look for things like airway narrowing, collapse of part of the lung (atelectasis), fluid, or infection sitting behind a partial obstruction. If infection looks likely, we may ask for a sputum sample. Very occasionally, we look for malignant cells in sputum, but to be honest, it is not the most reliable way to diagnose lung cancer.

If there is genuine concern about a blocked airway, we may discuss bronchoscopy. It lets us look directly at the airway and, in some cases, clear mucus, take samples, or both.

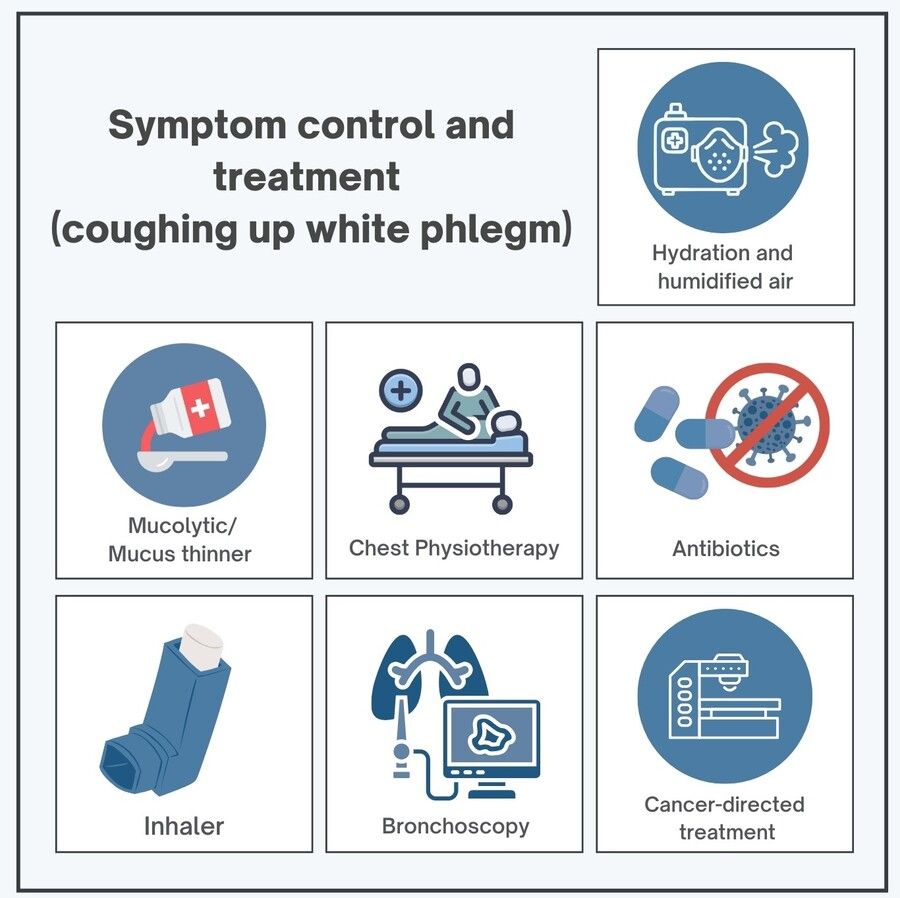

What helps (Symptom control and treatment)

The right treatment depends on the cause. Ultimately, we need to treat the cause of the phlegm in order to get it under control. Treatment options can include:

-

Hydration and humidified air, to thin secretions and make coughing more effective

-

Mucolytics (such as carbocisteine) if the sputum is thick and difficult to shift

-

Chest physiotherapy techniques for clearance

-

Antibiotics, if there is evidence of infection, especially post-obstructive infection

-

Inhalers if there is wheeze, asthma overlap, or COPD flare

-

Bronchoscopy to remove mucus plugs or relieve obstruction in selected cases

-

Cancer-directed treatment (radiotherapy, systemic treatment, sometimes stenting) if the main driver is tumour-related airway narrowing

To be honest, the “small” interventions often make a big difference day to day. Better clearance means less breathlessness, less coughing, and better sleep.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can white phlegm mean my lung cancer is getting worse?

Not usually. What matters is a clear change in cough, sputum, or breathlessness that needs checking.

What if the phlegm turns yellow or green?

It may be an infection, especially if you feel unwell or more breathless. Tell your team or GP.

What if there is blood in the phlegm?

Report any blood promptly. Heavy bleeding, faintness, or severe breathlessness needs urgent assessment.

Why is it worse at night or in the morning?

Often due to overnight pooling, reflux, or post-nasal drip. New or worsening night symptoms should be flagged.

When should I contact my cancer team rather than my GP?

If you are under a specialist team, contact them directly for new or worsening symptoms, especially breathlessness, fever, chest pain, or blood.

Next steps

If you are coughing up white phlegm and you have lung cancer, the key is not to diagnose yourself from the colour. Instead, watch for change, persistence, and associated symptoms. Then tell your team early so we can work out whether this is irritation, infection, obstruction, or a mix of the above.

About Dr. James Wilson

Dr. James Wilson is a consultant oncologist specialising in lung cancer and advanced radiotherapy. Based in Central London, he works full-time in private practice, aiming to provide rapid diagnosis, clear plans, and calm, practical guidance when time matters.